My family settled near Wartburg, Tennessee in 1845. I was born a short three years later in October of 1848. I grew up during a troubled time in the history of our country. Up until the time I left home, I expect that I ran into about as much trouble as any other boy in Morgan County. At least that’s how I felt at the time. We came up with Sunday school and church, as my mother was a good old-fashioned Campbellite. I had three brothers and four sisters, and you know what? Not even one of them acted as though he or she liked to go to church on Sundays. Personally, I had nothing in particular against going to church. If only it had not been for the raccoons, turkey, rabbits, ‘possums, skunks and other game of that kind running all about in the woods. All year long but especially during deer season, hunting kept me busy most nights through the week and on many Sundays. I felt it was my duty and responsibility to keep on proper terms with the wild game.

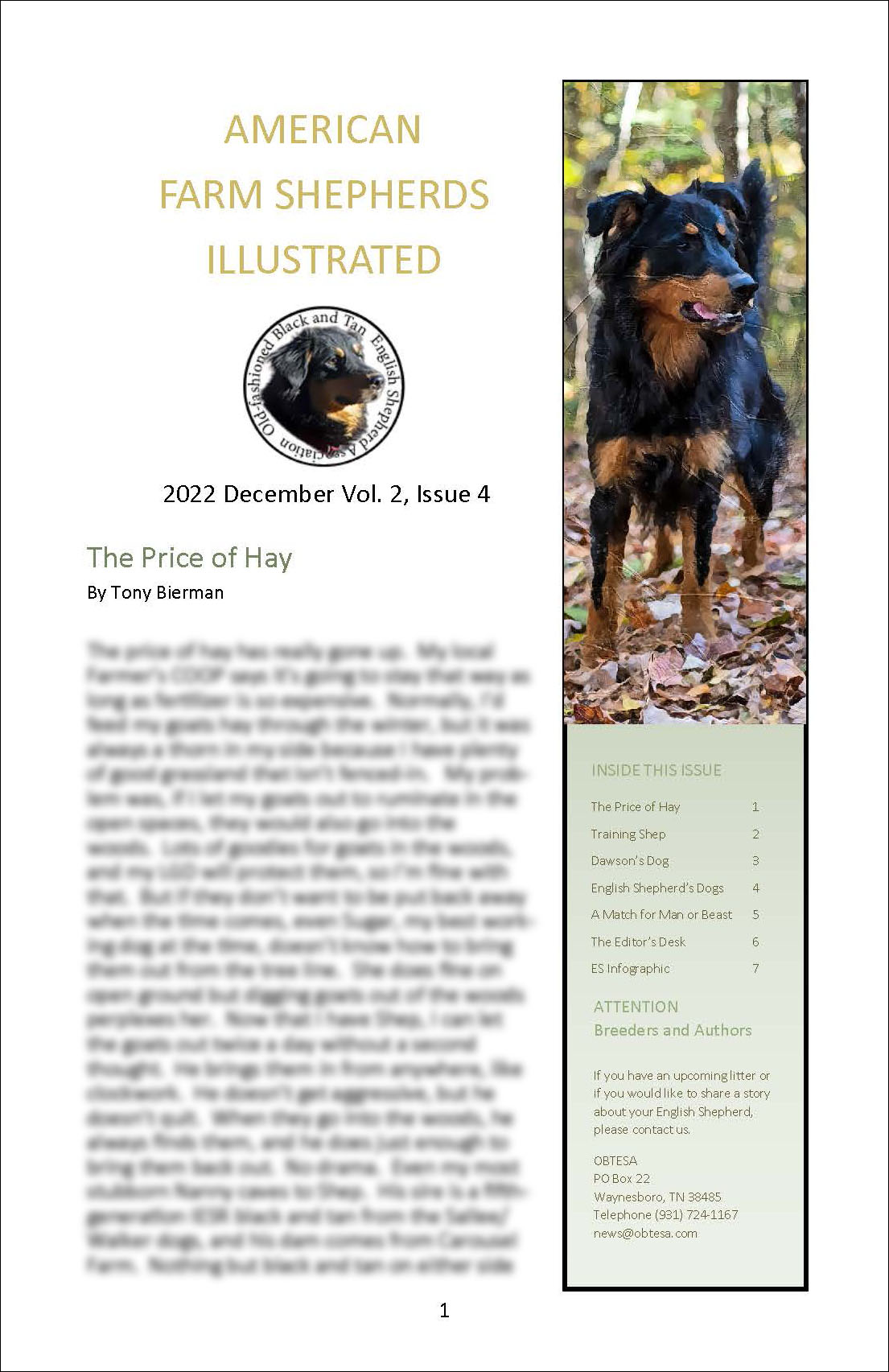

Whenever possible, I would steal out grandpa’s rifle, take the dog and hunt all day. I knew full well that when I did show back up at home I was in for a scolding from my mother or a regular thumping from dad. My mother was a tall, powerful woman. She would whip me while she herself cried, as if she was the one receiving each lash! In between tears, she would proclaim up to the Lord above about how much good she was trying to do in breaking me of my wicked ways. But don’t you know what would happen the minute a skunk, raccoon or fox came along during the night and carried off one of her chickens? Mom would wake me at first morning’s light, hand me the gun, tell me to take Old Shep and go kill the thieving varmint that had stolen her bird. Even when a neighbor would complain of losing a precious chicken, mother would tell them to send out her boy Tom and his Old Shep to bring home that guilty varmint’s pelt. To this day, I think mother thought Old Shep was of more importance against varmints than I was. But Old Shep and I knew different. I could climb any tree in Morgan County, dig frozen ground with a pick, and follow cold tracks in the mud or snow. But even so, there was never a better dog than Old Shep. Shep had a glossy black coat, a tan spot above each eye, and a tan bar across his chest. When he was a pup, Shep loved to chew walnuts. One time he swallowed a walnut whole and half choked himself to death. My older brother said little Shep might get real sick, but it all worked out in the end.

I always thought Shep could whip any dog in Tennessee. And at the time, I thought Tennessee was the whole world except maybe for Kentucky because one of the families at church was from there. But I had to fight many battles just to keep up the reputation of Old Shep. As he got older and wiser, Shep came to think I would help him and sometimes he’d just get whipped. When Shep got whipped, we both came home looking pretty used up. And whenever that happened, Shep would not leave my side for days. I can recall a family of boys named the Grinders who claimed to have the best raccoon dog who was also the toughest fighting dog in the world. Looking back now I think without a doubt that the Grinder boys’ dog must have been a good dog. But at the time, I sure did hate him. When the Grinder boys and I ran together, it always ended-up the same way. A dog fight between Old Shep and the Grinder dog, followed by a fist fight between Sam Grinder and me. Without fail, Old Shep and I went home pretty badly used up. Sam Grinder always said I helped Shep. And he would try to keep me from doing so. That’s when Sam and I would mix it up. I guess we fought a hundred times, and he always quit after he’d beaten me to his satisfaction. I could hardly even get a lick in sideways. That Grinder dog’s name was Flint. I guess because he was gray. My argument was always that Shep knew more than Flint. Just to illustrate, there was this time when Sam Grinder was up in a tree to shake off a raccoon for Flint to kill. Well, the limb broke, and down came Sam, Flint and the raccoon. The funny thing is, the Raccoon ran off and instead of chasing after it, Flint jumped on Sam! His own dog took off a piece of his ear, tore a hole in his arm and used Sam up pretty bad before he could even understand that Sam wasn’t the raccoon. I always claimed that Shep would have had more sense than to jump on me if I had ever been fool enough to fall out of a tree.

My mother was always anxious to have all her children in school during the winter months, and I had to go. Or at least I had to start out in that direction, anyway. But all the natural influences of the countryside were dead set against my acquiring very much of an education. During the summer, we had to go to work on the farm. Hard and long hours putting crops into the ground and tending to them. It all left for little time to go fishing and hunt bee trees. When winter first came and the work was done with all the crops brought in, I wanted to go and look after game. But I was ordered to go to school, I had to go. The first natural influence of any importance was that the schoolhouse was a country mile from our farmhouse. There was always snow or frost on the ground in the early morning, and on the walk to school I’d come across fresh varmint tracks crossing the trail to school. I never could pass by a fresh track. I would see one and notice that none of the other kids would pay attention to it. So, I would follow it and see which way it went. And then I would go on a little further, and then I would say to myself, “I will be late for school or get licked.” Then an overpowering desire to get that raccoon, ‘possum, rabbit or wild cat would overcome me. I would go back to the orchard behind the house and call for Old Shep. The stuff for school went into a hollow tree, and off for hunting we went. So, you can see, had the schoolhouse been nearer, I could have gotten there a great deal more often than I did.

My childhood ended in January of 1862 when a clash between Union and Confederate soldiers broke out near Wartburg. It was the first time, but not the last time, I had seen the wicked ways of war. My older brother was killed in the skirmish. He was only seventeen years old at the time. We were all upset. My mother cried a lot. She eventually lost two sons in that war, one for each side. It was the end of her. A few days after my first brother died, Shep and I came across some soldiers going along the road. Behind their wagons were two wounded men on one horse. One of them had a single-barreled scatter gun. I hollered out that a man who shot game with a scatter gun was no good. One of the wounded soldiers asked me if I called myself a man, and my answer caused him to get off his old horse. He handed his gun to the other soldier and we started to scrap. I was fourteen and he was only a few years older, and I held my own. The other soldier decided to jump off his horse and give me a kick in the jaw. But he never smiled again, because Old Shep sprang and caught him and threw him to the ground. That stopped the fight. I pulled Shep off the soldier and told them they had better get back on their old horse and go. I think I told them to go get some more soldiers if they wanted to win a fight. That’s when one of the soldiers picked up the scatter gun and shot poor Old Shep. Shep whined and I could scarcely believe such a thing had been done. The soldiers galloped off, and I carried Shep the quarter mile to home. He died in the barn that night. I believe that was the first and only real sorrow of my life.

Get AFSI, Our Quarterly Printed Newsletter