The Old-fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd is an important foundational strain of the English Shepherd landrace. In accordance with best practice for effective landrace management, the Old-fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd merits deliberate and carefully crafted intentional conservation that will benefit the landrace as a whole.

Background

“Landrace” refers to populations of animals that are isolated to a local area where local production goals and local physical environment drive selection. According to Sponenberg et. al[1]Managing Breeds for a Secure Future: Strategies for Breeders and Breed Associations 2nd Edition by Phillip Sponenberg, Alison Martin, and Jeannette Beranger, Landraces derive their unique genetic character from the usual combination of founder effect, isolation, natural selection, and human selection. Landraces achieve their genetic consistency and uniqueness by default rather than by design, even though some level of human selection is typical in most landraces. Founding event, subsequent isolation, and natural selection environment are the three basic factors that most determine the overall type and function of a landrace. All three are important, and all three must be considered when developing effective conservation programs for these unique and useful genetic resources. While landraces occur in all species, they are especially few in dogs, and these few therefore have great importance for wise conservation.

As history progresses and global development proceeds, the isolation that once protected a landrace disappears. Isolation is essential for a landrace, as it will otherwise fail to be genetically uniform to the extent that is necessary for it to serve as a useful genetic resource. The temptation to crossbreed landraces out of existence is generally more than can be resisted. Crossing can provide a quick, if temporary financial return, and can frequently become the strategy for the best short-term outcome. Unfortunately, the long-term outcome of such crossbreeding is usually below the productive potential of the original uncrossed landrace. This fact is usually discovered too late, after the original landrace is gone. The biggest hurdle to overcome with conservation of a landrace is when the cultural and physical space in which it developed has been changed dramatically. Isolation that protected the landrace diminishes to the point that it no longer ensures protection. So long as cultural, geographic, and infrastructural barriers isolated the landrace, it was safe in its original habitat for its original purpose. Conservation must therefore result from carefully crafted intentional efforts rather than by the default of isolation which can no longer realistically be achieved.

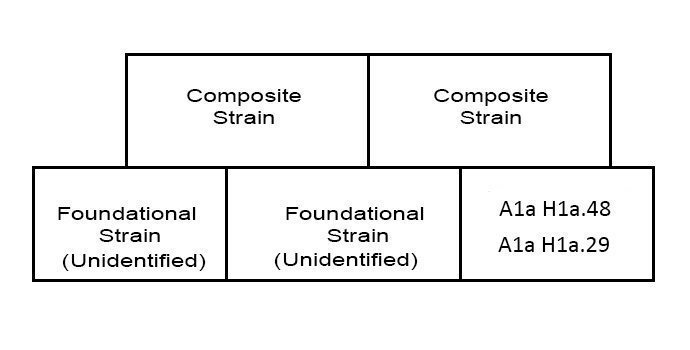

Landraces usually have a genetic organization very distinct from standardized breeds. Landraces are like a short, one or two-story building with many separate rooms. Each sub population (strain or line) is variably isolated from the others. In many cases, breeds organized in this manner compromise several herds that each persists in complete genetic isolation from one another. In addition to foundational strains, landraces have composites that are built from multiple foundational strains. These composites are like a second-story room built over the top of several first story rooms. The genetics from the foundational strains (first story rooms) provide the support structure for the composite strains (second story rooms).

Effectively, today’s existing English Shepherd Club is a breeders’ organization which primarily supports the composite strains of the breed. But as the primary breeders’ organization of a landrace breed, the ESC does currently or historically prioritize the isolation and conservation of foundational strains. This unfortunate oversight will have lasting consequences if not rectified internally or compensated for externally by other breed organizations.

The situation with the English Shepherd Club is not uncommon. Most landraces lack tightly organized breeder organizations. Lack of organization works well when isolation is ensured by limited infrastructure. As soon as infrastructure improves, non-deliberate isolation fails to function very well and more formal strategies for isolation and organization of landraces must be developed if these genetic resources are to survive.

Landrace conservation has many inherent challenges, not least of which is the very choice of which specific individuals should be included in the landrace. When classifying members of a foundational strain within a landrace, three of the most conclusive tools we can use are genotype, phenotype and history. In isolation, any one of these three investigations can be inconclusive. But when all three are used together, we can assert a classification with a reasonable amount of confidence.

Genotype of the Old-fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd

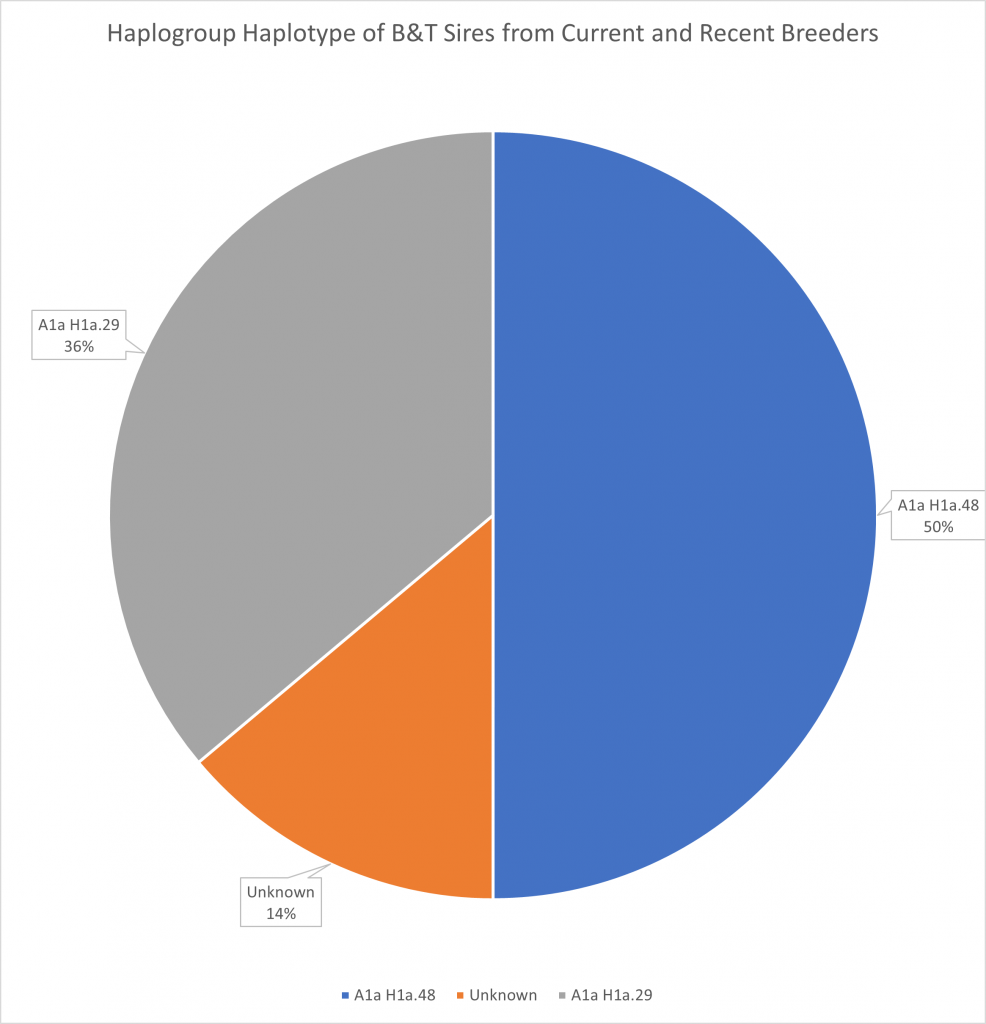

Sires from the Old-fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd consist predominantly of genotypes of the A1a H1a.48 and A1a H1a.29 haplogroup / haplotypes. Because most foundational strains in a landrace breed were started with only a few individual dogs, those foundational strains are dominated by only one or a few haplotypes.

| Sire | Strain |

| Carousel’s Calhoun | A1a H1a.48 |

| Carousel’s Joey Rifle | Unknown |

| Duke (sire of Oney’s Butch) | A1a H1a.48 |

| Maynard’s Duke | A1a H1a.48 |

| Maynard’s King Bob | A1a H1a.48 |

| Maynard’s King III | A1a H1a.48 |

| Maynard’s Prince | A1a H1a.48 |

| Miller’s Tennessee Tucker | A1a H1a.48 |

| Oney’s Butch | A1a H1a.48 |

| Oney’s Nick | A1a H1a.48 |

| Oney’s Ruff | A1a H1a.29 |

| Oney’s Sam | Unknown |

| Oney’s Smoke | A1a H1a.48 |

| Oney’s Toby | Unknown |

| Oney’s Ziggy | A1a H1a.48 |

| Raulston’s Roscoe | A1a H1a.48 |

| Rockhouse Hollow Remington | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Billy Bob | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Duke (Jr.) | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Jake | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Jo Jo | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Okla Boo | A1a H1a.48 |

| Sallee’s Rustie Jr. | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Sam | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Sambo | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sallee’s Smoky Bear | Unknown |

| Shepherd’s Rex Blaze | A1a H1a.29 |

| Sherling’s Ace | Unknown |

| Sherling’s Jack | A1a H1a.48 |

| Sherling’s Dan | A1a H1a.48 |

| Sonny Tucker McCarty | A1a H1a.48 |

| Wheelbarger’s Ebony | A1a H1a.29 |

| Wheelbarger’s Tiny | A1a H1a.29 |

| Whippoorwill’s Jethro | A1a H1a.29 |

| Whippoorwill’s Johnny Reb | A1a H1a.48 |

| Whippoorwill’s Poplar Creek Bandit | A1a H1a.48 |

Phenotype of the Old-fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd

The Blankenship Standard for the Old-Fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd[2]Standard for English Shepherds is a simplified version of Stodghill’s Standard of the English Shepherd Dog. The Stodghill standard was published on page 10 of the Spring 1969 issue of Animal Research Magazine.[3]Standard of the English Shepherd Dog, Stodghill’s Animal Research Magazine, 1969 Spring Issue, page 10

History of the Old-fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd

The article The Blankenships’ Best Friend by John Blankenship was published in the English Shepherd Club of America’s Who’s Who Breeder Manual. In The Blankenships’ Best Friend, John Blankenship states that “Trotting beside my father, Charles B. Blankenship, as he rode to town on the old gray mare in Wilson County, Tennessee, some seventy years ago, the Black and Tan family pet was on hand to drive home cattle, sheep or other livestock purchased.” This statement by Mr. Blankenship establishes that his family was using black and tan farm dogs prior to the turn of the 20th century. Wilson County is directly north of and adjacent to Rutherford County in Tennessee.

Also in The Blankenships’ Best Friend, John Blankenship states that “Mother, too, recalls mention of the Shepherd dogs that her father and her grandfather used to help in rounding up the stock. My Wife’s people migrated to Cannon County, Tennessee, from Virginia and North Carolina. Both of her parents, Altte Simmons Wilson and Aubrey H. Wilson, (childhood sweethearts) were raised on the farmlands near Woodbury, Tennesssee. Her father’s helper in capturing the wild hogs that roamed the woods was Jack, a sturdy Shepherd.” Cannon County is east of and adjacent to Rutherford County. Woodbury, TN is located in Cannon County.

In one more passage of The Blankenships’ Best Friend, John Blankenship states that “we bought a pair of Black and Tan pups to help herd the dairy and beef cattle, the sheep and hogs. The male was christened “Captain Ned”, in memory of the Ned my father once owned. Like his ancestor in color and type, the new Ned began in our hearts where the other left off.” Here again, Mr. Blankenship reaffirms that his family was using black and tan farm dogs prior to the turn of the 20th century.

The article English Shepherds in the News by Mrs. C.M. Bend was originally published in the English Shepherd Club of America’s Who’s Who Breeder Manual. In the article English Shepherds in the News it is stated that Tom D. Stodghill “came back to Middle Tennessee last week, this time trying to find other cattle dogs such as his grandfather took to Texas with him 60-odd years ago.” Sixty years prior to the article would be approximately the turn of the 20th century.

Also In the article English Shepherds in the News, Tom D. Stodghill is quoted as saying “Some Middle Tennessee families owning these dogs did not even know what breed the dogs were. Only that the dogs were excellent for handling livestock. But color, markings, and other features as well as the performance of these dogs show definitely that they are of the English Shepherd breed, and have bred true down through the years.”

References

| ↑1 | Managing Breeds for a Secure Future: Strategies for Breeders and Breed Associations 2nd Edition by Phillip Sponenberg, Alison Martin, and Jeannette Beranger |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Standard for English Shepherds |

| ↑3 | Standard of the English Shepherd Dog, Stodghill’s Animal Research Magazine, 1969 Spring Issue, page 10 |